There are a million blog posts on photography depth of field (DOF). This one makes a million and one! If writing this will help me, and hopefully someone else, understand it better, it will be worth it.

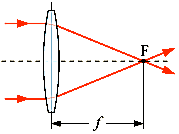

We assume that a typical camera lens is fixed in space and represents the properties of a “thin convex lens in air”. We say an object, such as a distant mountain, is at infinity if light from it enters the lens along a ray perpendicular, or nearly perpendicular, to the lens plane. The principal focal point is that point behind the lens that an object at infinity (on the axis of the lens) focuses to. The focal length is the distance from the center of the lens to the principal focal point of the lens. This is illustrated below.

Define the object plane to be the plane of the object you are photographing parallel to the plane of the lens) and want to look sharp in your photo. (Again, the object is assumed to be on the axis of the lens.) The light from the object converges behind the lens to a small region called the image. The image plane is a plane (parallel to the lens) which intersects this image region. You want the plane of the digital sensor (or camera film) to be at or very near the image plane, or else the photo will not have the object in focus.

We assume that the camera is a projective transformation from the plane of the object to the plane of the digital sensor. In other words, we assume that the camera has the property that if it focuses on a (stright) line or circle then it captures a line or circle on the film or digital sensor. (Of course, in reality, the lens imperfections and the light diffraction have an effect, but this hypothesis is nearly true in many cases.)

Consider an object at infinity (say, some distant mountains) in the plane of the plane of your lens. Suppose your camera’s digital sensor is located in the same plane as the image plane, so that the mountains will be in focus in your camera. The distance from the lens to the sensor plane is the focal length . Consider the light entering your lens from a small disk (also on the axis of the lens) at a distance

in front of the lens. This light will meet the sensor plane but its image in the photo, depending on the value of

, may or may not be in focus. If the disk is relatively small in diameter then its blurred image on the photo is sometimes called a circle of confusion. Concretely speaking, the circle of confusion measures the maximum diameter on an 8′′ × 10′′ photo for which there is an acceptable blur in the image of the disk. Suppose now that the distance between the lens and sensor plane (say that the lens, along with the disk in front of it, are fixed but the sensor plane is translated backwards) is increased until this small disk is in focus in the photo. Call this new distance between the lens and the sensor plane

.

Lemma 1. The focal length , the distance from the lens to the object to photograph

, and the distance from lens to the image focus plane

are then related by the lens equation

.

Example: As is decreased,

must be increased. For example, consider a normal lens for a 35 mm camera with a focal length of

mm. To focus an object 1 m away (

mm), we solve for

. Therefore, the lens must be moved 2.6 mm further away from the image plane, to

mm.

The depth of field (DOF) is the portion of a scene that appears sharp in the image. More precisely, it is the area near the object plane in which the circles of confusion are acceptably small (where “acceptably small” has some precise pre-defined meaning, e.g., 0.2mm for a photo blown up to an 8′′ × 10′′ print). Although a lens can precisely focus at only one distance, the decrease in sharpness is gradual on either side of the focused distance, so that within the DOF, the unsharpness is imperceptible under normal viewing conditions. See the image below for an example of an image with a “small” (or “short”) DOF.

The lens aperture is the circular opening in the lens allowing light to pass through. The actual diameter of opening is called the effective aperture. By convention, the aperture is measured as a quotient relative to the focal length . For example, the aperture

is an opening which is half the focal length, so if

mm then the effective aperture would be a disc of diameter 25mm. In general, if the aperture is

(read “the f-stop is N”, where

) then

is called the f-number or f-stop. Two apertures (or f-stops) are said to differ by a full stop if they differ by a factor of

. Usually the stop numbers fall into the sequence

which might be rounded up or down to

The larger f-stop is, the smaller the aperture.

For more details, see for example:

- Jeff Conrad, Depth of field in depth, preprint 2006. Available at: http://www.largeformatphotography.info/.

- L. Evens, View camera geometry, preprint, 2008.

- R. E. Wheeler, Notes on view camera geometry, preprint, 2003.

You must be logged in to post a comment.