Introductory example of checking

We may use the field  as the basis for a simple illustrative exercise in the actual procedure of checking. The general of the operations involved will thus be made clear, so far as modus operandi is concerned, and we shall be enabled to discuss more easily the pertinent mathematical details.

as the basis for a simple illustrative exercise in the actual procedure of checking. The general of the operations involved will thus be made clear, so far as modus operandi is concerned, and we shall be enabled to discuss more easily the pertinent mathematical details.

It is easy to set up telegraphic codes of high capacity using combinations of four letters each which are not required to be pronounceable. In fact, a sufficiently high capacity may be obtained when only

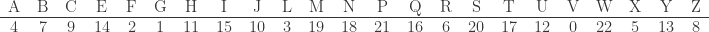

twenty-three letters of the alphabet are used at all. Hence we can omit any three letters whose Morse equivalents (dot-dash) are most frequently used. Let us suppose that we have before us a code of this kind which employs the letters

and avoids, for reasons stated of for some good reason, the three letters

Suppose that, by prearrangement with telegraphic correspondents, the letters used are paired in

an arbitrary, but fixed, way with the thwenty-three elements of  .

.

Let the pairings be, for instance:

or, in numerical arrangement:

A four-letter group (code word), such as EZRA or XTYP, will indicate a definite entry of a specific page of a definite code volume, several such volumes being perhaps employed in the code. An entry will, in general, be a phrase of sentence, or a group of phrases or sentences, commonly occurring in the class of messages for which the code has been constructed.

Suppose that we have agreed to provide, in our messages, three-letter checks upon groups of twelve letters; in other words, to check in one operation a sequence of three four-letter code words. The twelve letters of the three code words are thus expanded to fifteen; but we send just three telegraphic words — three combinations of five letters, each of which is, in general, unpronounceable.

For illustration, let the first three code words of a message be:

The corresponding sequence of paired elements in  is:

is:

This is our operand sequence  :

:

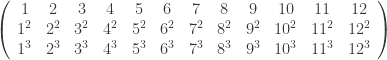

Let us determine the checking matrix  by using as reference matrix

by using as reference matrix

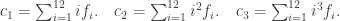

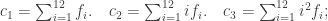

Thus the  are to be

are to be

or

Referring to the multiplication table of  , we easily compute the

, we easily compute the  .

.

For the first element  , of the operant sequence

, of the operant sequence  , write

, write

For the second element  place a sheet of paper (or a ruler) under the second row

place a sheet of paper (or a ruler) under the second row

of the multiplication table, and in that row read:  in column

in column  ,

,  in column

in column  ,

,  in column

in column  . we now have a second line for the tabular scheme:

. we now have a second line for the tabular scheme:

For the third element  place a sheet of paper (or a ruler) under the third row

place a sheet of paper (or a ruler) under the third row

of the multiplication table, and in that row read:  in column

in column  ,

,  in column

in column  ,

,  in column

in column  . We now have the scheme:

. We now have the scheme:

The fifth, eighth, and tenth rows of the table will not be used, since

. The complete scheme is readily found to be:

. The complete scheme is readily found to be:

We have  ,

,  ,

,  .

.

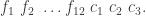

We transmit, of course, the sequence of letters paired, in our system of communications, with the elements of the sequence,

Thus we transmit the sequence of letters: XTYP VZRV HVHH RIF; but we may conveniently agree to transmit it in the arrangement:

or in some other arrangement which employs only three telegraphic words (unpronounceable five letter groups).

We could have used other reference matrices, but we shall not stop to discuss this point. We may remark, however, that if the matrix

had been adopted, the checking elements would have been

and their evaluation would have been accomplished with equal

ease by means of the multiplication table of  .

.

You must be logged in to post a comment.