Backstory: Lester Saunders Hill wrote unpublished notes, about 40 pages long, probably in the mid- to late 1920s. They were titled “The checking of the accuracy of transmittal of telegraphic communications by means of operations in finite algebraic fields”. In the 1960s this manuscript was given to David Kahn by Hill’s widow. The notes were typewritten, but mathematical symbols, tables, insertions, and some footnotes were often handwritten. The manuscript is being LaTeXed “as we speak”. I thank Chris Christensen, the National Cryptologic Museum, and NSA’s David Kahn Collection, for their help in obtaining these notes. Many thanks also to Rene Stein of the NSA Cryptologic Museum library and David Kahn for permission to publish this transcription. Comments by transcriber will look his this: [This is a comment. – wdj]. I used Sage (www.sagemath.org) to generate the tables in LaTeX.

Here is just the second section of his paper. I hope to post more later. (Part 1 is here.)

Secton 2: Lemmas concerning algebraic fields

Familiarity with primary notions in the theory of finite algebraic fields, and of their algebraic extensions, will naturally be assumed here. Reference is made, however, to Steinitz [St], Dickson [D], Scorza [Sc]. But several points which will be needed very frequently in the following pages are summarized here in a series of lemmas. These lemmas assert properties of any algebraic field, whether it be finite or not.

Lemma 1:

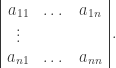

Let  denote an algebraic field. Let the coeefficients

denote an algebraic field. Let the coeefficients  in the system of equations

in the system of equations

be elements of  . Let

. Let  denote the value, in

denote the value, in  , of the determinant

, of the determinant

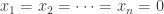

The system of equations has a solution other than

if and only if  .

.

Lemma 2:

Let  denote an algebraic field. Let the coeefficients in the system of equations

denote an algebraic field. Let the coeefficients in the system of equations

be elements of  , and let

, and let  be less than

be less than  . Then the system of equations certainly has a solution other than

. Then the system of equations certainly has a solution other than

Lemma 3:

Let  denote an algebraic field. Let the

denote an algebraic field. Let the  and the

and the  denote elements of

denote elements of  and let at least one of the

and let at least one of the  be different from zero. Consider the determinant

be different from zero. Consider the determinant

If  (Footnote: The case

(Footnote: The case  does not concern us.) then the system of equations

does not concern us.) then the system of equations

has one and only one solution.

Evidently, when solutions exist for the systems of equations considered in the forgoing three lemmas, such solutions lie entirely in the field  .

.

The lemma which follows is particularly useful. It is an immediate corollary of Lemma 1.

Lemma 4:

Let  denote an algebraic field. Let the

denote an algebraic field. Let the  denote elements of

denote elements of  . Then if

. Then if

we can determine at least one sequence of elements  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , which are not necessarily distinct but certainly are not all equal to zero, such that

, which are not necessarily distinct but certainly are not all equal to zero, such that

Lemma 5:

The algebraic equation of $ th degree

th degree

with coefficients in the algebraic field  , can not have more than

, can not have more than  roots in

roots in  .

.

Most of the considerations of the present paper will depend, more or less directly, upon these five lemmas.

References:

[D] L. E. Dickson, Linear groups with an exposition of the Galois field theory, B. G. Teubner, Leipzig, 1901. Available here:

http://archive.org/details/lineargroupswith00dickuoft

[Sc] G. Scorza, Corpi numerici e algebre, Giuseppe Principato, 1921.

[St] E. Steinitz, Algebraische theorie der korper, Journal fur die reine und angew. Mathamtik 137(1910)167-308.

You must be logged in to post a comment.