Lacking a suitable reference, here is a short bio of this fascinating researcher compiled by claude.

Early Life and Emigration from Germany

Hans Berliner was born in Berlin, Germany in 1929, into a family with a remarkable technological heritage. His great-uncle, Emile Berliner, was the inventor of the gramophone and held the patent on the disc recording format—a technology that would eventually prove superior to Thomas Edison’s cylindrical records and become the ancestor of all subsequent disc-based media formats, including hard drives and modern optical discs. The Berliner family had been involved in telephone technology at the turn of the century, with Emile owning the patent on the carbon receiver for the telephone and establishing a telephone company in Hanover, Germany.

Young Hans entered the German public school system just as Adolf Hitler was rising to power. The first hour of each school day was devoted to “religion” (meaning Christianity) and National Socialism—activities in which Berliner was not permitted to participate. He was also excluded from joining his friends in the Hitler Youth. “I was told that I was Jewish, and they didn’t want me,” Berliner later recalled. “That was quite a shock, and I guess that’s one of those things that sort of grows you up a little bit.”

Despite the oppressive political atmosphere, Germany in the 1930s remained a stimulating environment for a child interested in science. Berliner remembered it as “probably the best place in the world” for such interests. “The Germans were full of inventiveness and managed to produce things that were very, very good,” he recalled. He particularly remembered a metal wind-up toy car equipped with a working servomechanism that could sense when it was about to run off a ledge and automatically steer away—a sophisticated device for a child’s toy in 1935. German kindergarteners were reportedly “three years ahead” of their American counterparts in mathematics, and these formative years had a lasting positive effect on Berliner’s intellectual development.

The family’s fortunes changed dramatically in 1936 when two visitors from the United States came to stay with the Berliners. Seven-year-old Hans soon learned that the family would be leaving Germany. A nephew of Uncle Emile, Joseph Sanders, had arranged for approximately ten members of the extended family to emigrate to America. In 1937, the Berliner family arrived in the Washington, D.C. area, speaking very little English and with thick German accents.

Berliner’s father held a master’s degree in electrical engineering, while his mother had essentially no education beyond high school. Berliner would later describe his home environment as not particularly intellectual, with his parents “more just interested in surviving.” However, one of the most formative experiences of his life occurred before he was three years old, when his grandmother gave him a chalkboard with letters and numbers around the edges. He began making words and doing sums, and from that point on, learning came naturally. “I just wanted to know everything about everything,” he recalled.

Education and the Discovery of Chess

Berliner doggedly pursued his studies at Henry D. Cooke Elementary School in Washington, eventually graduating with the top grammar marks in his class. One of his fellow students was Carlos Fuentes, who would become a famous Mexican novelist and essayist. Fuentes vividly remembered Berliner as the “extremely brilliant boy” with “deep-set, bright eyes—a brilliant mathematical mind—and an air of displaced courtesy that infuriated the popular, regular, feisty, knickered, provincial, Depression-era sons-of-bitches.”

At age 11 and 12, Berliner read every book in the adult section of the library about astronomy, developing what he felt was phenomenal knowledge of the subject. He even reached the point where he recognized that certain theories about the formation of the solar system were patently wrong because they violated physical principles he understood. However, there was no outlet for such precocious knowledge—no school could handle a 12-year-old with advanced expertise, and no special programs existed for gifted children at that time.

Into this intellectual vacuum came chess. At age 13, Berliner was at a summer camp when rain forced everyone indoors. He noticed other children playing a game on a board that wasn’t checkers. He asked about the rules, learned them, and by the end of the day was already beating one of the other players. “Chess seemed a natural,” he recalled. “In a way, I sometimes thought maybe that was not the best path to go, but that was the one that presented itself.” Chess offered something that astronomy could not: a domain where a young person could immediately compete in the adult world.

Berliner progressed rapidly in chess, becoming a master by 1949 or 1950. He would later represent the United States at the 10th Chess Olympiad in Helsinki, Finland in 1952, where he met his future wife, a Finnish woman whom he married in 1954.

Academic and Professional Struggles

After high school, Berliner entered George Washington University to pursue a degree in physics with ambitions of becoming a top-notch physicist. However, he had no understanding of the academic path required—the need for a Ph.D. and years of study. He was one of the top physics students, but he grew bored with the program and began “majoring in bridge” rather than attending classes. Before long, his grades had plummeted, and the draft beckoned. He entered the U.S. Army in early 1951 and served with the German occupation forces. Throughout his tour of duty, Berliner continued to play chess, including one exhibition where he simultaneously played eight games against one of the top German teams—and won them all.

Upon his return to civilian life, Berliner was reluctant to return to college. It was Isador Turover, a fellow European immigrant and former top U.S. chess player who had become a successful lumber magnate in Washington, who set Berliner straight. Turover, whom Berliner had met through chess circles, told the younger man in no uncertain terms, “You will finish your degree.” He hired Berliner into his lumber company so he could earn money to pay his way through college, since there was no family money for education and Berliner had never secured a scholarship.

Unable to return to physics due to his low grade point average, Berliner switched to psychology, naively believing that with a psychology degree he could “hang out a shingle as a psychologist and start counseling people.” Again fate intervened. A classmate who worked at the Naval Research Laboratory told Berliner, “We need people like you where I work.” This led to a position in what was then called “human engineering” or “engineering psychology”—a predecessor to modern interface design and human factors research.

Early Career and First Encounters with Computers

Starting at the Naval Research Laboratory in 1954, Berliner worked on human engineering problems, such as ensuring that Navy pilots didn’t pull the wrong lever and eject themselves when trying to lower the landing gear. During this period, he had his first brush with computers. A colleague at the lab was helping to build NRL’s own computer—one of very few computers in existence at that time—and suggested they might write a chess program together. They talked about it and even did a few preliminary things, but the project never got off the ground. Berliner had read the foundational articles by Claude Shannon and by Newell and Simon about computer chess in Scientific American, but he “didn’t have the foggiest notion how to implement it.”

From the Naval Research Lab, Berliner moved to Martin Company in Denver, then to General Electric’s Missile and Space Vehicle Division in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania—which he described as “one of the finest places I’ve ever operated,” with more talented people than perhaps even Carnegie Mellon—and finally to IBM in Bethesda, Maryland. Throughout these moves, his specialty remained human factors work, which he did not consider particularly fulfilling. “My pay was skyrocketing, but I had an awful lot of spare time,” he later recalled.

Rise to Chess Prominence

hroughout the 1950s, Berliner’s chess ranking continued to climb. He became a Senior Master with a rating in the 2420-2440 range, placing him among the top ten players in the United States. He played regularly in the U.S. Invitational Championship, and in the year Bobby Fischer won the title for the first time, Berliner finished fifth and drew with Fischer.

His reputation became especially strong in correspondence chess—games played through the mail—where his systematic approach and analytical mind could shine without the time pressure of tournament play. From 1965 to 1968, Berliner served as World Correspondence Chess Champion, winning his first championship with a remarkable record of 12 wins and 4 draws in 16 games, a margin of victory three times better than any previous champion. He remained the top-ranked U.S. correspondence chess player until 2005, long after he stopped competing.

Murray Campbell, who would later work on IBM’s Deep Blue, observed that Berliner wasn’t a “star” player in the mold of Bobby Fischer or Garry Kasparov, but achieved chess greatness “using a very systematic approach and a lot of hard work.” Berliner “had competitive fire” and an analytical mind that enabled him to beat players “who might very well have been more talented than him.”

Carnegie Mellon and Computer Chess Research

While at IBM in the late 1960s, Berliner began thinking seriously about computer chess. He had never written a program in his life, so he had to learn programming while developing his first chess program. Called “J. Biit” (an acronym for “Just Because It Is There”), it was written in PL/1 and played in the first U.S. Computer Chess Championship in 1970, finishing around the middle of the field.

In 1967, Berliner met future Nobel laureate Herbert Simon at a technical meeting. Simon, who in 1956 had famously predicted that within ten years a computer would become world chess champion, was still interested in chess-playing computers. He offered Berliner a job at Carnegie Mellon University, but Berliner turned down the position of researcher. “If I’m going to come there, you’ve got to put me on the student track,” he insisted. At nearly 40 years old, feeling that he wanted to do “something worthwhile” with his life, Berliner was accepted into CMU’s Computer Science Department as a doctoral student in 1969.

Berliner found CMU to be a “good” but “chaotic” environment, with the department “up on wobbly feet.” The founding department head, Alan Perlis, was “an amazing, wonderful person” with “a desire for progress and truth that was very, very commendable.” Newell allowed Berliner to begin his thesis work on computer chess even before completing the rigorous qualifying examinations.

For his doctoral dissertation, titled “Chess as Problem Solving,” Berliner developed a chess program called CAPS that incorporated what he called the “causality facility.” This mechanism dragged back descriptions of tactical events through the search tree, allowing the program to reason about why certain moves failed and what characteristics a move would need to prevent similar failures. The program could figure out how to block threats without trying every possibility, simply by reasoning about what was required.

However, even as Berliner refined CAPS, he became convinced that rule-based approaches had fundamental limitations. “I had a set of rules that were limited,” he explained. “They were the most important things—maybe 80 percent—but that’s nothing. The other 20 percent includes the things the top players know how to do. That’s why they’re the top players.” Newell and Simon kept encouraging him to create more rules, but Berliner recognized that something crucial was missing: the intuitive understanding that allowed grandmasters to evaluate positions at a glance.

The B* Algorithm and Backgammon

While searching for new research directions, Berliner learned backgammon from his father-in-law and decided to write a program for this simpler game. His initial attempts encountered a familiar problem: the program would reach a certain point and then bog down, “trying to optimize things that it should have forgotten about.” At some point, when a player was clearly winning, the strategy should change—the program needed to recognize when transitions were coming.

Berliner hit upon the idea of using fuzzy logic—still a novel concept in the 1970s—to assign different rules “weights” or “application factors” based on their relative importance at each stage of the game. The resulting program, called BKG, began winning games it would have previously lost. In July 1979, BKG became the first computer program to defeat a reigning world champion in any board game when it beat backgammon champion Luigi Villa.

One of the highlights of Berliner’s research was the B* (“B-star”) algorithm, designed to emulate what he called the “jumping around” process in human thought. Rather than using traditional best-first or depth-first searches with arbitrary termination criteria, B* assigned an “optimistic” and a “pessimistic” score to each node. The algorithm continued searching a branch as long as the pessimistic value of the best node was no worse than the optimistic value of its sibling nodes. B* found paths that were sufficient for a task rather than theoretically “perfect” ones—emulating how a human chess master stops searching when finding a move that seems clearly best.

As Andy Palay, one of Berliner’s students, observed, B* represented “a much more directed search toward what appear to be the most promising paths” compared to simple best-first searches.

HiTech: A Chess-Playing Machine

In 1983, Berliner embarked on what he would later describe as one of the best periods of his professional life. His student Carl Ebeling proposed building a chess-playing machine using the then-novel technology of very-large-scale integrated (VLSI) circuits. Ebeling custom-designed a processor to generate chess moves, and the resulting machine, named HiTech, used 64 of these processors—one for each square of the chessboard—operating in parallel.

The enthusiasm for HiTech was extraordinary. “Everyone wanted to know what the latest developments were, and if they could help,” Berliner recalled. Volunteers from inside and outside CMU’s Computer Science Department took turns wire-wrapping connections in a third-floor lab in Wean Hall. With a hardware budget of only about five thousand dollars, the team scavenged parts and bought 32K memory chips at twenty or thirty dollars each.

A working prototype was completed in 1984. HiTech could consider 175,000 positions per second—compared to the one or two moves per second a top human player might examine. The machine also incorporated pattern recognizers that Ebeling designed to identify specific positional features, such as trapped bishops, pawn structures, and king safety issues. These pattern recognizers “sat like gargoyles on the edge of the thing watching the positions go by,” detecting problems and opportunities that pure calculation might miss.

“From the very beginning, I could see that it had the potential—maybe not every single time—it had the potential to play better than any device that existed,” Berliner recalled. The team worked hundred-hour weeks, with Monday morning meetings to discuss progress and problems. “Every week it got better. Every week the machine played better than it did the week before; now that’s incredible, that’s truly amazing.”

In October 1985, HiTech won Pittsburgh’s Gateway Open chess competition, earning the rank of “master.” That same year it won the ACM tournament for chess programs. The machine went on to win the Pennsylvania State Championship three consecutive years—something Berliner himself had never achieved as a human player. By 1987, HiTech was ranked 190th in the United States and was the only computer among the top 1,000 players, with a rating around 2440—Senior Master level.

One particularly memorable achievement was a four-game match against grandmaster Arnold Denker, which HiTech won 3.5 to 0.5. “It outplayed him in every game, in every single game. It completely beat him,” Berliner recalled.

Rivalry and the Road to Deep Blue

While Berliner’s team was developing HiTech, fellow CMU graduate students Feng-hsiung Hsu and Thomas Anantharaman began work on another chess-playing computer called ChipTest. Like HiTech, it relied on VLSI technology, but it was significantly faster—by 1987, ChipTest was searching 500,000 moves per second.

Daniel Sleator, a CMU professor who had founded the Internet Chess Club, noted that having two competing chess systems developed simultaneously at CMU “reflects a number of important things about the culture in the Computer Science Department. For one thing, there is a tremendous amount of respect for the work of graduate students. The faculty gives them the benefit of the doubt, and in many cases, including this one, it pays off.”

However, the relationship between the teams deteriorated over time. “There was some tension that never got resolved, and there were some hard feelings in terms of the competition between the two groups,” Campbell acknowledged. ChipTest evolved into Deep Thought, which won the World Computer Chess Championship in 1989. IBM subsequently hired Hsu, Campbell, and Anantharaman, and the machine that became Deep Blue eventually defeated world champion Garry Kasparov in 1997.

Legacy and Perspective

In retrospect, Berliner was characteristically blunt about the field he helped pioneer. Computer chess was “a research dead-end” as far as artificial intelligence was concerned, he concluded. “The whole AI thesis was wrong. AI researchers thought more knowledge would do everything.” Instead, more powerful processors and machine-learning techniques powered by statistical analysis, rather than human-devised rules, proved capable of cracking data-intensive problems in speech, image analysis, and data retrieval.

However, those who studied Berliner’s work disagreed with his self-assessment. “He covered a lot of ground, and he achieved excellence in all of those areas,” said Campbell. Jonathan Schaeffer, a professor at the University of Alberta who led the team that created the unbeatable Chinook checkers program, noted that Berliner “has a legacy of excellent papers that contain insights, algorithms and new ideas that aren’t as common today as they should be. People continue to reference his work when they realize there are other ways to do things, and then they point at Hans.”

Schaeffer observed that “most scientists aren’t willing to take the kinds of risks that Hans would take. But that’s why his papers are still around, while the papers of his contemporaries are long gone and forgotten.”

Berliner’s willingness to question conventional wisdom led to controversy, including his accusation that Russian computer scientist and chess grandmaster Mikhail Botvinnik had committed fraud by manipulating published results. Schaeffer and others reviewed Berliner’s evidence and concluded that Botvinnik had indeed massaged his results. Similarly, Berliner’s 1999 book The System: A World Champion’s Approach to Chess attracted sharp criticism from some reviewers, but the attacks left him unbowed.

His former students remembered not just his demanding standards but his generosity. “Working with Hans was a lot of fun,” recalled Palay. “There was a great deal of graciousness, both on a personal level and a professional level. He was very much concerned with making sure that he was treating me well, not just as his student, but as a person.” Ebeling noted that Berliner “led by example more than anything else. There was a constant attention to detail, and he was always thinking, looking out for the next idea that might work.”

Berliner retired from Carnegie Mellon in 1998. His advice to students: “Learn all the substantive knowledge that you can. In the final analysis, all knowledge hangs together, and the more you know, the easier it will be to make good decisions in the future. Learn something that has value—something quantitative, hopefully. Have something you can do that someone else will want to pay you for—a product. If you don’t have that, it’s going to be tough for you.”

Hans Berliner passed away on January 13, 2017, at the age of 87, leaving behind a remarkable legacy as a world chess champion, a pioneer in computer game-playing, and a scientist who was never afraid to challenge conventional wisdom in pursuit of truth.

Main References

Interview with Gardner Hendrie on 2005-03-07, Oral history of Hans Berliner, CHM Reference number X3131.2005, Computer History Museum, 2005.

J. Togyer, The Iconoclast, in The Link: The Magazine of the Carnegie Mellon University School of Computer Science, May 7, 2012.

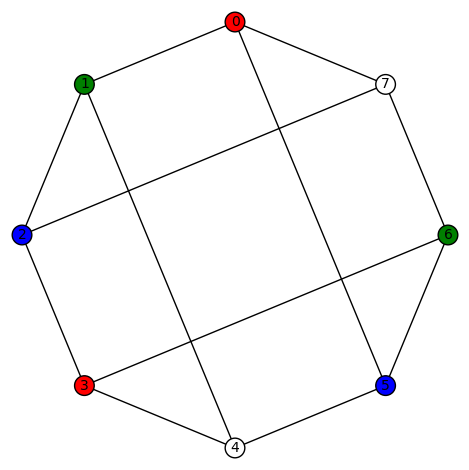

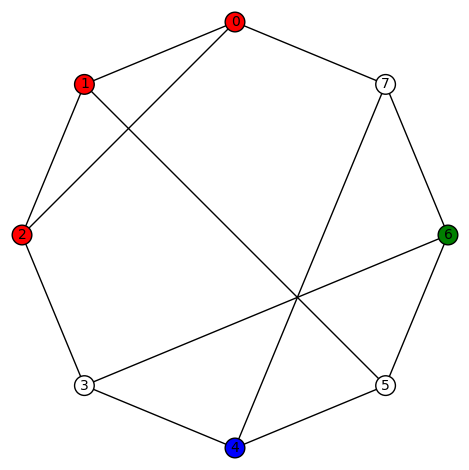

(the automorphism group of K4, ie the symmetric group of degree 4, acts on the colors {0,1,2,3} and produces 24 total plots), and

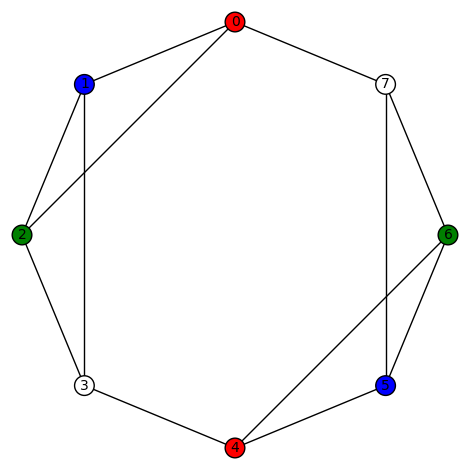

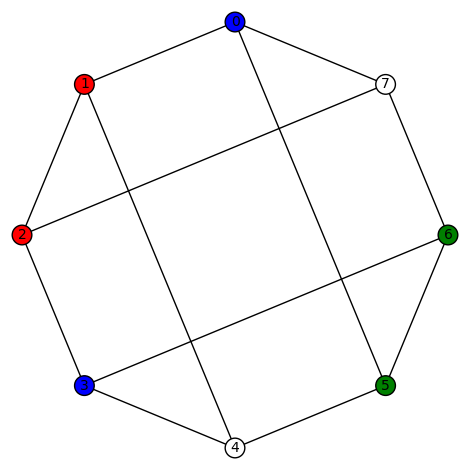

(the automorphism group of K4, ie the symmetric group of degree 4, acts on the colors {0,1,2,3} and produces 24 total plots), and  (again, the automorphism group of K4, ie the symmetric group of degree 4, acts on the colors {0,1,2,3} and produces 24 total plots). There are 8 non-trivial harmonic morphisms to

(again, the automorphism group of K4, ie the symmetric group of degree 4, acts on the colors {0,1,2,3} and produces 24 total plots). There are 8 non-trivial harmonic morphisms to  and

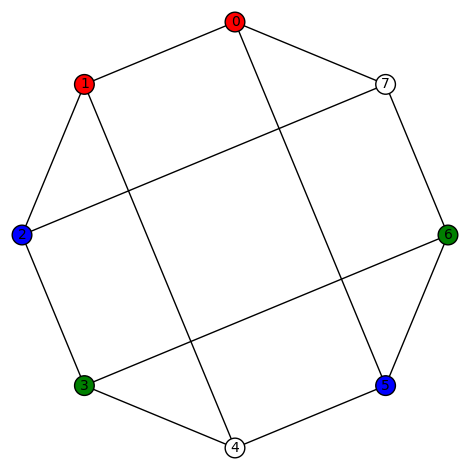

and  Here the automorphism group of K4, ie the symmetric group of degree 4, acts on the colors {0,1,2,3}, while the automorphism group of the graph

Here the automorphism group of K4, ie the symmetric group of degree 4, acts on the colors {0,1,2,3}, while the automorphism group of the graph

Let

Let

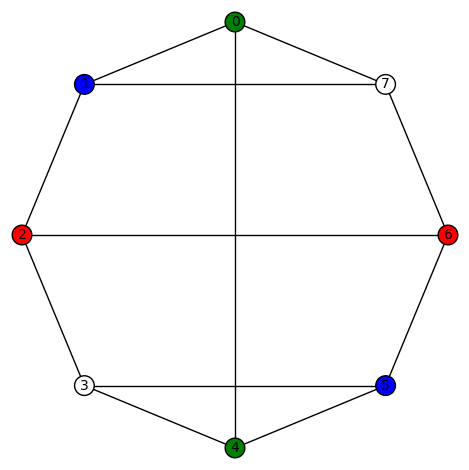

A few examples of a non-trivial harmonic morphism to Diamond:

A few examples of a non-trivial harmonic morphism to Diamond: and

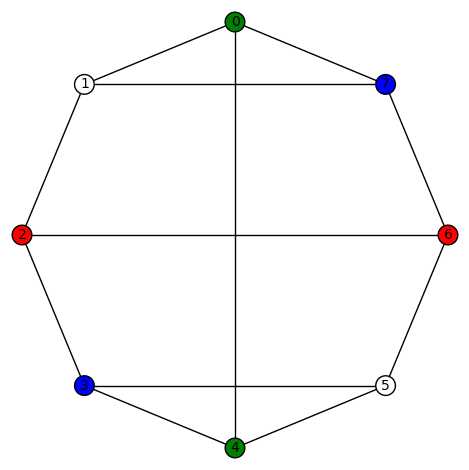

and A few examples of a non-trivial harmonic morphism to C4:

A few examples of a non-trivial harmonic morphism to C4:

You must be logged in to post a comment.