A state of a baseball game is a 10-tuple (s0,s1,s2,s3,j,vs,hs,tab,b,s), where

- s0 denotes the number of outs (represented as one of the integers 0,1,2)

- s1 is 0 if there is no runner on 1st base and 1 otherwise,

- s2 is 0 if there is no runner on 2nd base and 1 otherwise,

- s3 is 0 if there is no runner on 3rd base and 1 otherwise,

- j is the inning number (represented usually as one of the integers 1, 2, . . . , 9, but it can have a larger value if the score is tied),

- vs is the current score (number of runs) of the visiting team,

- hs is the current score of the home team,

- tab is the “team at bat” – 0 for visitor and 1 for home,

- b counts the balls to the batter,

- s counts the strikes.

For simplicity, we will always work within a given inning and omit the variables past the inning number variable. Therefore, for the remainder, regard the set of all possible states as a list of 4-tuples. These states can be listed in a 8×3 array:

(0,0,0,0), (1,0,0,0), (2,0,0,0),

(0,1,0,0), (1,1,0,0), (2,1,0,0),

(0,0,1,0), (1,0,1,0), (2,0,1,0),

(0,0,0,1), (1,0,0,1), (2,0,0,1),

(0,1,1,0), (1,1,1,0), (2,1,1,0),

(0,1,0,1), (1,1,0,1), (2,1,0,1),

(0,0,1,1), (1,0,1,1), (2,0,1,1),

(0,1,1,1), (1,1,1,1), (2,1,1,1)

Similarly, the so-called run expectancy matrix (denoted REM or RE24) is formed by examining the 24 states of a baseball game and entering the number of expected runs into each state. (This matrix depends on the year the games were played and on the ballpark. Interactive RE24 visualizations and downloadable datasets can be found on the FanGraphs website, https://blogs.fangraphs.com/introducing-the-batter-specific-run-expectancy-tool/ .) We are only looking at the states here.

There are often several ways to transition from one state to another. For example, the transition (0,0,0,0) -> (0,0,0,1) could be from a (triple) hit by the batter followed by running the bases to 3rd base. In the reverse order, the transition (0,1,1,1) -> (0,0,0,0) is also possible, when the batter hits a (grand slam) homerun. We list (most of) the possible transitions below. Omitted are the “self-transitions”, such as (1) (0,0,0,0) -> (0,0,0,0) when the batter hits a homerun, or (2) (0,1,0,0) -> (0,1,0,0) when the batter hits a single but gets an RBI from the runner on 1st base advancing all the way home. (Question: These self-transitions yield loops in the associated graph but should they be allowed for wider applications?) As indicated above, we also omit transitioning to the next inning (3 outs).

Transitions from (0,0,0,0): (0,1,0,0), (0,0,1,0), (0,0,0,1), (1,0,0,0).

Transitions from (0,1,0,0): (0,0,0,0), (0,0,1,0), (0,0,0,1), (0,1,1,0), (0,1,0,1), (0,0,1,1), (1,1,0,0), (1,0,1,0), (1,0,0,1), (2,0,0,0).

Transitions from (0,0,1,0): (0,0,0,0), (0,1,0,0), (0,0,0,1), (0,1,1,0), (0,1,0,1), (0,0,1,1), (1,1,0,0), (1,0,1,0), (1,0,0,1), (2,0,0,0).

Transitions from (0,0,0,1): (0,0,0,0), (0,1,0,0), (0,0,1,0), (0,1,0,1), (0,0,1,1), (1,1,0,0), (1,0,1,0), (1,0,0,1), (2,0,0,0).

Transitions from (0,1,1,0): (0,0,0,0), (0,1,0,0), (0,0,1,0), (0,0,0,1), (0,1,0,1), (0,0,1,1), (0,1,1,1), (1,1,0,0), (1,0,1,0), (1,0,0,1), (1,1,1,0), (1,1,0,1), (1,0,1,1), (2,0,0,0), (2,1,0,0), (2,0,1,0), (2,0,0,1).

Transitions from (0,1,0,1): (0,0,0,0), (0,1,0,0), (0,0,1,0), (0,0,0,1), (0,1,1,0), (0,0,1,1), (0,1,1,1), (1,1,0,0), (1,0,1,0), (1,0,0,1), (1,1,1,0), (1,1,0,1), (1,0,1,1), (2,0,0,0), (2,1,0,0), (2,0,1,0), (2,0,0,1).

Transitions from (0,0,1,1): (0,0,0,0), (0,1,0,0), (0,0,1,0), (0,0,0,1), (0,1,1,0), (0,1,0,1), (0,1,1,1), (1,1,0,0), (1,0,1,0), (1,0,0,1), (1,1,1,0), (1,1,0,1), (1,0,1,1), (2,0,0,0), (2,1,0,0), (2,0,1,0), (2,0,0,1).

Transitions from (0,1,1,1): (0,0,0,0), (0,1,0,0), (0,0,1,0), (0,0,0,1), (0,1,1,0), (0,1,0,1), (0,0,1,1), (1,1,0,0), (1,0,1,0), (1,0,0,1), (1,1,1,0), (1,1,0,1), (1,0,1,1), (2,0,0,0), (2,1,0,0), (2,0,1,0), (2,0,0,1), (2,1,1,0), (2,1,0,1), (2,0,1,1).

Transitions from (1,0,0,0): (1,1,0,0), (1,0,1,0), (1,0,0,1), (2,0,0,0).

Transitions from (1,1,0,0): (1,0,0,0), (1,0,1,0), (1,0,0,1), (1,1,1,0), (1,1,0,1), (1,0,1,1), (2,0,0,0), (2,1,0,0), (2,0,1,0), (2,0,0,1).

Transitions from (1,0,1,0): (1,0,0,0), (1,1,0,0), (1,0,0,1), (1,1,1,0), (1,1,0,1), (1,0,1,1), (2,0,0,0), (2,1,0,0), (2,0,1,0), (2,0,0,1).

Transitions from (1,0,0,1): (1,0,0,0), (1,1,0,0), (1,0,1,0), (1,1,0,1), (1,0,1,1), (2,0,0,0), (2,1,0,0), (2,0,1,0), (2,0,0,1).

Transitions from (1,1,1,0): (1,0,0,0), (1,1,0,0), (1,0,1,0), (1,0,0,1), (1,1,0,1), (1,0,1,1), (1,1,1,1), (2,0,0,0), (2,1,0,0), (2,0,1,0), (2,0,0,1), (2,1,1,0), (2,1,0,1), (2,0,1,1).

Transitions from (1,1,0,1): (1,0,0,0), (1,1,0,0), (1,0,1,0), (1,0,0,1), (1,1,1,0), (1,0,1,1), (1,1,1,1), (2,0,0,0), (2,1,0,0), (2,0,1,0), (2,0,0,1), (2,1,1,0), (2,1,0,1), (2,0,1,1).

Transitions from (1,0,1,1): (1,0,0,0), (1,1,0,0), (1,0,1,0), (1,0,0,1), (1,1,0,1), (1,1,0,1), (1,1,1,1), (2,0,0,0), (2,1,0,0), (2,0,1,0), (2,0,0,1), (2,1,1,0), (2,1,0,1), (2,0,1,1).

Transitions from (1,1,1,1): (1,0,0,0), (1,1,0,0), (1,0,1,0), (1,0,0,1), (1,1,1,0), (1,1,0,1), (1,0,1,1), (2,0,0,0), (2,1,0,0), (2,0,1,0), (2,0,0,1), (2,1,1,0), (2,1,0,1), (2,0,1,1), (2,1,1,1).

Transitions from (2,0,0,0): (2,1,0,0), (2,0,1,0), (2,0,0,1).

Transitions from (2,1,0,0): (2,0,0,0), (2,0,1,0), (2,0,0,1), (2,1,1,0), (2,1,0,1), (2,0,1,1).

Transitions from (2,0,1,0): (2,0,0,0), (2,1,0,0), (2,0,0,1), (2,1,1,0), (2,1,0,1), (2,0,1,1).

Transitions from (2,0,0,1): (2,0,0,0), (2,1,0,0), (2,0,1,0), (2,1,1,0), (2,1,0,1), (2,0,1,1).

Transitions from (2,1,1,0): (2,0,0,0), (2,1,0,0), (2,0,1,0), (2,0,0,1), (2,1,0,1), (2,0,1,1), (2,1,1,1).

Transitions from (2,1,0,1): (2,0,0,0), (2,1,0,0), (2,0,1,0), (2,0,0,1), (2,1,1,0), (2,0,1,1), (2,1,1,1).

Transitions from (2,0,1,1): (2,0,0,0), (2,1,0,0), (2,0,1,0), (2,0,0,1), (2,1,1,0), (2,1,0,1), (2,1,1,1).

Transitions from (2,1,1,1): (2,0,0,0), (2,1,0,0), (2,0,1,0), (2,0,0,1), (2,1,1,0), (2,1,0,1), (2,0,1,1).

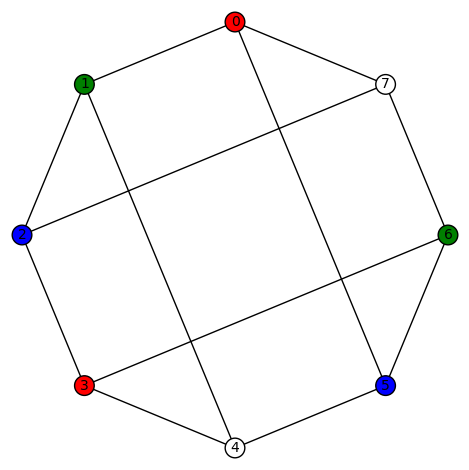

The graph with vertices being the 24 states and edges being those determined by the above neighborhoods, has 24 vertices, 182 edges, and degree of each state is given as follows:

(0, 0, 0, 0), 8

(0, 0, 0, 1), 11

(0, 0, 1, 0), 11

(0, 0, 1, 1), 17

(0, 1, 0, 0), 11

(0, 1, 0, 1), 17

(0, 1, 1, 0), 17

(0, 1, 1, 1), 20

(1, 0, 0, 0), 9

(1, 0, 0, 1), 18

(1, 0, 1, 0), 18

(1, 0, 1, 1), 18

(1, 1, 0, 0), 18

(1, 1, 0, 1), 18

(1, 1, 1, 0), 18

(1, 1, 1, 1), 15

(2, 0, 0, 0), 22

(2, 0, 0, 1), 18

(2, 0, 1, 0), 18

(2, 0, 1, 1), 12

(2, 1, 0, 0), 18

(2, 1, 0, 1), 12

(2, 1, 1, 0), 12

(2, 1, 1, 1), 8

Note the state of maximal degree (of 22) is (2,0,0,0).

and

. Months of computer searches resulted in a number of conjectures that were used to shape the material in the book.

You must be logged in to post a comment.