Backstory: Lester Saunders Hill wrote unpublished notes, about 40 pages long, probably in the mid- to late 1920s. They were titled “The checking of the accuracy of transmittal of telegraphic communications by means of operations in finite algebraic fields”. In the 1960s this manuscript was given to David Kahn by Hill’s widow. The notes were typewritten, but mathematical symbols, tables, insertions, and some footnotes were often handwritten. I thank Chris Christensen, the National Cryptologic Museum, and NSA’s David Kahn Collection, for their help in obtaining these notes. Many thanks also to Rene Stein of the NSA Cryptologic Museum library and David Kahn for permission to publish this transcription. Comments by transcriber will look like this: [This is a comment. – wdj]. I used Sage (www.sagemath.org) to generate the tables in LaTeX.

Here is just the eighth section of his paper. I hope to post more later. (Part 7 is here.)

Section 8: Examples of finite fields

The reader is probably accustomed to the congruence notation in dealing with finite fields. It may therefore be helpful to insert here two simple examples of finite fields, and to employ, in these concrete cases, the notations of the present paper rather than those of ordinary number theory.

Example: A small field in which the number  is not prime.

is not prime.

Let the elements of the field be the symbols or marks

and let us define, by means of two appended tables, the field of operations of addition and multiplcation in such a manner that the marks  ,

,  represent respectively the zero and the unit elements of the field.

represent respectively the zero and the unit elements of the field.

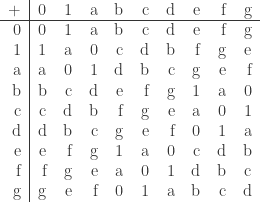

These tables are

Denoting by  an arbitrary element of this field, we see that negatives and reciprocals of the elements of the field are as shown in the scheme:

an arbitrary element of this field, we see that negatives and reciprocals of the elements of the field are as shown in the scheme:

The use of notations is easily illustrated. Thus, for example, we note that the determinant

of the system of equations

vanishes. For, expanding the determinant by the elements of its first row, we obtain

Hence the system has solutions other than  . By the usual methods, it is quickly found that one solution is (

. By the usual methods, it is quickly found that one solution is ( ,

,  ,

,  ). The general solution is (

). The general solution is ( ,

,  ,

,  ), where

), where  denotes an element of the field.

denotes an element of the field.

For further practice, we note that the system of equations

has exactly one solution. It may be found by the standard method employing quotients of determinants [What we call today Cramer’s rule – wdj.]. or as follows:

[11 lines of hand calculations are omitted. – wdj]

The solution is  ,

,  .

.

As noted in Section 1, the number  of the elements of a finite algebraic field is either a prime integer greater than

of the elements of a finite algebraic field is either a prime integer greater than  , or a positive integral power of such an integer. In the present example, we have

, or a positive integral power of such an integer. In the present example, we have  . It may be observed in passing that if

. It may be observed in passing that if  is any element of a finite field for which

is any element of a finite field for which

that is, for which  is a power of

is a power of  , then in that field

, then in that field  .

.

Example: A small field in which the number  of elements is prime.

of elements is prime.

Let  ,

,  ,

,

be

be  symbols or marks, and let

symbols or marks, and let  be a prime integer. We readily define a finite algebraic field of which the elements are the

be a prime integer. We readily define a finite algebraic field of which the elements are the  . To this end, we regard $f_i$ as associated with the integer

. To this end, we regard $f_i$ as associated with the integer  which we shall call the “affix” of the mark

which we shall call the “affix” of the mark  . Understanding that of course

. Understanding that of course  is the “smallest integer” in any set of non-negative integers which includes

is the “smallest integer” in any set of non-negative integers which includes  , we now define as follows:

, we now define as follows:

Sum: The sum of the marks  and

and  is given by the formula

is given by the formula

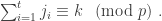

where  is the smallest non-negative integer satisfying

is the smallest non-negative integer satisfying

Product: The product of the marks  and

and  is given by the formula

is given by the formula

where  is the smallest non-negative integer satisfying

is the smallest non-negative integer satisfying

With the operations of addition and multiplication thus defined, our set of  marks constitutes, as is well-known, an algebraic field. We call a field of this type a “primary” field.

marks constitutes, as is well-known, an algebraic field. We call a field of this type a “primary” field.

In a primary field, an addition table would never be required. For we note that, if

are  elements of our field then

elements of our field then

where  is the smallest non-negative integer satisfying the congruence

is the smallest non-negative integer satisfying the congruence

Naturally, a similar statement holds for the product. We have

where  is the smallest non-negative integer satisfying the congruence

is the smallest non-negative integer satisfying the congruence

In the foregoing definitions, any of the terms of a sum, or of the factors of a product, may, of course, be equal.

When dealing with a primary field, we may obviously replace the marks of the fields by their affixes. We do this in the example which follows.

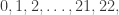

Example: Let the marks of a finite field be

the field containing  elements. An addition table is not needed. The multiplication table is as follows:

elements. An addition table is not needed. The multiplication table is as follows:

Products in which  is a factor all vanish, and therefore not shown in the table.

is a factor all vanish, and therefore not shown in the table.

In any algebraic field, the elements  and

and  are negatives —

are negatives —  ,

,  — when

— when  . In the present example, therefore, two marks

. In the present example, therefore, two marks  and

and  are negatives if

are negatives if

where  are momentarily regarded as ordinary integers of familiar arithmetic.

are momentarily regarded as ordinary integers of familiar arithmetic.

Negatives, reciprocals, squares and cubes are shown by the scheme:

This field will be called  . We shall use it in illustrating our checking operations.

. We shall use it in illustrating our checking operations.

Familiarity with the notations here employed may be gained by working out several exercises of simple type. Thus, the reader may note that the polynomial in

has the three roots  , so that we may write

, so that we may write

He may make the important observation that no two different elements of  have the same cube, and that this was to be expected. For the equation

have the same cube, and that this was to be expected. For the equation

where  denotes any element (other than

denotes any element (other than  ) of

) of  , can be written

, can be written

the factor  being irreducible in

being irreducible in  . The fact that

. The fact that

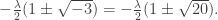

has no root in  may be shown by “completing the square”, and thus noting that the roots would have to be of the form

may be shown by “completing the square”, and thus noting that the roots would have to be of the form

But reference to the scheme of squares given above discloses that  is not the square of an element in

is not the square of an element in  .

.

from

randomly until

first exceeds

. What is the probability that this happens on the fourth draw? That is, what is the probability that

and

?

?

You must be logged in to post a comment.