Let f be a Boolean function on  . The Cayley graph of f is defined to be the graph

. The Cayley graph of f is defined to be the graph

,

,

whose vertex set is  and the set of edges is defined by

and the set of edges is defined by

.

.

The adjacency matrix  is the matrix whose entries are

is the matrix whose entries are

,

,

where b(k) is the binary representation of the integer k.

Note  is a regular graph of degree wt(f), where wt denotes the Hamming weight of f when regarded as a vector of values (of length

is a regular graph of degree wt(f), where wt denotes the Hamming weight of f when regarded as a vector of values (of length  ).

).

Recall that, given a graph  and its adjacency matrix A, the spectrum Spec(

and its adjacency matrix A, the spectrum Spec( ) is the multi-set of eigenvalues of A.

) is the multi-set of eigenvalues of A.

The Walsh transform of a Boolean function f is an integer-valued function over  that can be defined as

that can be defined as

A Boolean function f is bent if  (this only makes sense if n is even). The Hadamard transform of a integer-valued function f is an integer-valued function over

(this only makes sense if n is even). The Hadamard transform of a integer-valued function f is an integer-valued function over  that can be defined as

that can be defined as

It turns out that the spectrum of  is equal to the Hadamard transform of f when regarded as a vector of (integer) 0,1-values. (This nice fact seems to have first appeared in [2], [3].)

is equal to the Hadamard transform of f when regarded as a vector of (integer) 0,1-values. (This nice fact seems to have first appeared in [2], [3].)

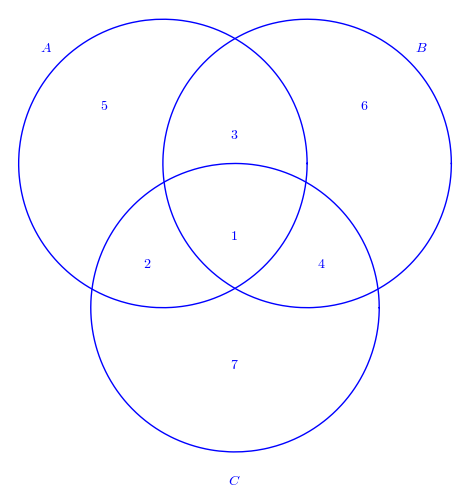

A graph is regular of degree r (or r-regular) if every vertex has degree r (number of edges incident to it). We say that an r-regular graph  is a strongly regular graph with parameters (v, r, d, e) (for nonnegative integers e, d) provided, for all vertices u, v the number of vertices adjacent to both u, v is equal to

is a strongly regular graph with parameters (v, r, d, e) (for nonnegative integers e, d) provided, for all vertices u, v the number of vertices adjacent to both u, v is equal to

e, if u, v are adjacent,

d, if u, v are nonadjacent.

It turns out tht f is bent iff  is strongly regular and e = d (see [3] and [4]).

is strongly regular and e = d (see [3] and [4]).

The following Sage computations illustrate these and other theorems in [1], [2], [3], [4].

Consider the Boolean function  given by

given by  .

.

sage: V = GF(2)^4

sage: f = lambda x: x[0]*x[1]+x[2]*x[3]

sage: CartesianProduct(range(16), range(16))

Cartesian product of [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15],

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15]

sage: C = CartesianProduct(range(16), range(16))

sage: Vlist = V.list()

sage: E = [(x[0],x[1]) for x in C if f(Vlist[x[0]]+Vlist[x[1]])==1]

sage: len(E)

96

sage: E = Set([Set(s) for s in E])

sage: E = [tuple(s) for s in E]

sage: Gamma = Graph(E)

sage: Gamma

Graph on 16 vertices

sage: VG = Gamma.vertices()

sage: L1 = []

sage: L2 = []

sage: for v1 in VG:

....: for v2 in VG:

....: N1 = Gamma.neighbors(v1)

....: N2 = Gamma.neighbors(v2)

....: if v1 in N2:

....: L1 = L1+[len([x for x in N1 if x in N2])]

....: if not(v1 in N2) and v1!=v2:

....: L2 = L2+[len([x for x in N1 if x in N2])]

....:

....:

sage: L1; L2

[2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2,

2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2,

2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2,

2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2,

2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2]

[2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2,

2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2,

2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2,

2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2,

2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2,

2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2,

2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2,

2, 2, 2, 2]

This implies the graph is strongly regular with d=e=2.

sage: Gamma.spectrum()

[6, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, -2, -2, -2, -2, -2, -2, -2, -2, -2]

sage: [walsh_transform(f, a) for a in V]

[4, 4, 4, -4, 4, 4, 4, -4, 4, 4, 4, -4, -4, -4, -4, 4]

sage: Omega_f = [v for v in V if f(v)==1]

sage: len(Omega_f)

6

sage: Gamma.is_bipartite()

False

sage: Gamma.is_hamiltonian()

True

sage: Gamma.is_planar()

False

sage: Gamma.is_regular()

True

sage: Gamma.is_eulerian()

True

sage: Gamma.is_connected()

True

sage: Gamma.is_triangle_free()

False

sage: Gamma.diameter()

2

sage: Gamma.degree_sequence()

[6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6]

sage: show(Gamma)

# bent-fcns-cayley-graphs1.png

Here is the picture of the graph:

sage: H = matrix(QQ, 16, 16, [(-1)^(Vlist[x[0]]).dot_product(Vlist[x[1]]) for x in C])

sage: H

[ 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1]

[ 1 -1 1 -1 1 -1 1 -1 1 -1 1 -1 1 -1 1 -1]

[ 1 1 -1 -1 1 1 -1 -1 1 1 -1 -1 1 1 -1 -1]

[ 1 -1 -1 1 1 -1 -1 1 1 -1 -1 1 1 -1 -1 1]

[ 1 1 1 1 -1 -1 -1 -1 1 1 1 1 -1 -1 -1 -1]

[ 1 -1 1 -1 -1 1 -1 1 1 -1 1 -1 -1 1 -1 1]

[ 1 1 -1 -1 -1 -1 1 1 1 1 -1 -1 -1 -1 1 1]

[ 1 -1 -1 1 -1 1 1 -1 1 -1 -1 1 -1 1 1 -1]

[ 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1]

[ 1 -1 1 -1 1 -1 1 -1 -1 1 -1 1 -1 1 -1 1]

[ 1 1 -1 -1 1 1 -1 -1 -1 -1 1 1 -1 -1 1 1]

[ 1 -1 -1 1 1 -1 -1 1 -1 1 1 -1 -1 1 1 -1]

[ 1 1 1 1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 1 1 1 1]

[ 1 -1 1 -1 -1 1 -1 1 -1 1 -1 1 1 -1 1 -1]

[ 1 1 -1 -1 -1 -1 1 1 -1 -1 1 1 1 1 -1 -1]

[ 1 -1 -1 1 -1 1 1 -1 -1 1 1 -1 1 -1 -1 1]

sage: flist = vector(QQ, [int(f(v)) for v in V])

sage: H*flist

(6, -2, -2, 2, -2, -2, -2, 2, -2, -2, -2, 2, 2, 2, 2, -2)

sage: A = matrix(QQ, 16, 16, [f(Vlist[x[0]]+Vlist[x[1]]) for x in C])

sage: A.eigenvalues()

[6, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, -2, -2, -2, -2, -2, -2, -2, -2, -2]

Here is another example:  given by

given by  .

.

sage: V = GF(2)^3

sage: f = lambda x: x[0]*x[1]+x[2]

sage: Omega_f = [v for v in V if f(v)==1]

sage: len(Omega_f)

4

sage: C = CartesianProduct(range(8), range(8))

sage: Vlist = V.list()

sage: E = [(x[0],x[1]) for x in C if f(Vlist[x[0]]+Vlist[x[1]])==1]

sage: E = Set([Set(s) for s in E])

sage: E = [tuple(s) for s in E]

sage: Gamma = Graph(E)

sage: Gamma

Graph on 8 vertices

sage:

sage: VG = Gamma.vertices()

sage: L1 = []

sage: L2 = []

sage: for v1 in VG:

....: for v2 in VG:

....: N1 = Gamma.neighbors(v1)

....: N2 = Gamma.neighbors(v2)

....: if v1 in N2:

....: L1 = L1+[len([x for x in N1 if x in N2])]

....: if not(v1 in N2) and v1!=v2:

....: L2 = L2+[len([x for x in N1 if x in N2])]

....:

sage: L1; L2

[2, 0, 2, 2, 2, 2, 0, 2, 2, 2, 0, 2, 2, 2, 2, 0, 0, 2, 2, 2, 2, 0, 2, 2, 2, 0, 2, 2, 2, 2, 0, 2]

[2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2]

This implies that the graph is not strongly regular, therefore f is not bent.

sage: Gamma.spectrum()

[4, 2, 0, 0, 0, -2, -2, -2]

sage:

sage: Gamma.is_bipartite()

False

sage: Gamma.is_hamiltonian()

True

sage: Gamma.is_planar()

False

sage: Gamma.is_regular()

True

sage: Gamma.is_eulerian()

True

sage: Gamma.is_connected()

True

sage: Gamma.is_triangle_free()

False

sage: Gamma.diameter()

2

sage: Gamma.degree_sequence()

[4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4]

sage: H = matrix(QQ, 8, 8, [(-1)^(Vlist[x[0]]).dot_product(Vlist[x[1]]) for x in C])

sage: H

[ 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1]

[ 1 -1 1 -1 1 -1 1 -1]

[ 1 1 -1 -1 1 1 -1 -1]

[ 1 -1 -1 1 1 -1 -1 1]

[ 1 1 1 1 -1 -1 -1 -1]

[ 1 -1 1 -1 -1 1 -1 1]

[ 1 1 -1 -1 -1 -1 1 1]

[ 1 -1 -1 1 -1 1 1 -1]

sage: flist = vector(QQ, [int(f(v)) for v in V])

sage: H*flist

(4, 0, 0, 0, -2, -2, -2, 2)

sage: Gamma.spectrum()

[4, 2, 0, 0, 0, -2, -2, -2]

sage: A = matrix(QQ, 8, 8, [f(Vlist[x[0]]+Vlist[x[1]]) for x in C])

sage: A.eigenvalues()

[4, 2, 0, 0, 0, -2, -2, -2]

sage: show(Gamma)

# bent-fcns-cayley-graphs2.png

Here is the picture:

REFERENCES:

[1] Pantelimon Stanica, Graph eigenvalues and Walsh spectrum of Boolean functions, INTEGERS 7(2) (2007), #A32.

[2] Anna Bernasconi, Mathematical techniques for the analysis of Boolean functions, Ph. D. dissertation TD-2/98, Universit di Pisa-Udine, 1998.

[3] Anna Bernasconi and Bruno Codenotti, Spectral Analysis of Boolean Functions as a Graph Eigenvalue Problem, IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTERS, VOL. 48, NO. 3, MARCH 1999.

[4] A. Bernasconi, B. Codenotti, J.M. VanderKam. A Characterization of Bent Functions in terms of Strongly Regular Graphs, IEEE Transactions on Computers, 50:9 (2001), 984-985.

[5] Michel Mitton, Minimal polynomial of Cayley graph adjacency matrix for Boolean functions, preprint, 2007.

[6] ——, On the Walsh-Fourier analysis of Boolean functions, preprint, 2006.

of index

.

which is to be transmitted.

,

, where

,

, the errors

and

being, of course, elements of the finite field

. If

(resp.,

) is correctly transmitted then the error

(resp.,

) vanishes, and

(resp.,

).

errors, all of which affect the

(the

being supposed correctly transmitted).

of the

, the errors being

,

. Since the

have been correctly transmitted, the mutilated message can not be in check unless

. Hence the message will fail to check, and the presence of error will be disclosed, unless the

errors

satisfy the system of equations

, of which the determinant is

, so that $\Delta \not=0$. It follows, by Lemma 1, that the system (S) has no solution other than

, for

. Hence

errors, confined to the

, can not escape disclosure if the reference matrix

is of index

. By the same argument, applied a fortiori, a set of less than

errors, confined to the

, will certainly be disclosed when

is of index

.

is of index

, we can make the following statement:

is transmitted with errors not affecting the

, and not more than

in number, the presence of error will infallibly be disclosed.

is of index

.

You must be logged in to post a comment.